For much of Minnesota’s history, winter roads looked like winter roads.

Snow-packed streets, visible ice, and slower driving were simply part of the season. People planned extra time, followed plow tracks, and understood that winter travel required caution. The idea that pavement should be black and bare during or shortly after a snowstorm is a relatively recent expectation, and one that is now carrying significant water quality consequences.

I recently had the opportunity to sit down with Klay Eckles, a retired public works director and engineer with more than 40 years of experience working across multiple communities in Washington County. He currently serves on the board of the Brown’s Creek Watershed District and has seen firsthand how winter road and ice management practices have evolved—and intensified—over the decades.

“Back in the 1960s, we used chains and studded tires,” Klay recalled. “I remember as a kid sitting in the car, seeing ice on the freeway, and following two narrow tire tracks where the studs had worn through to bare pavement. But those studs and chains were destroying roadways, so eventually they were outlawed.”

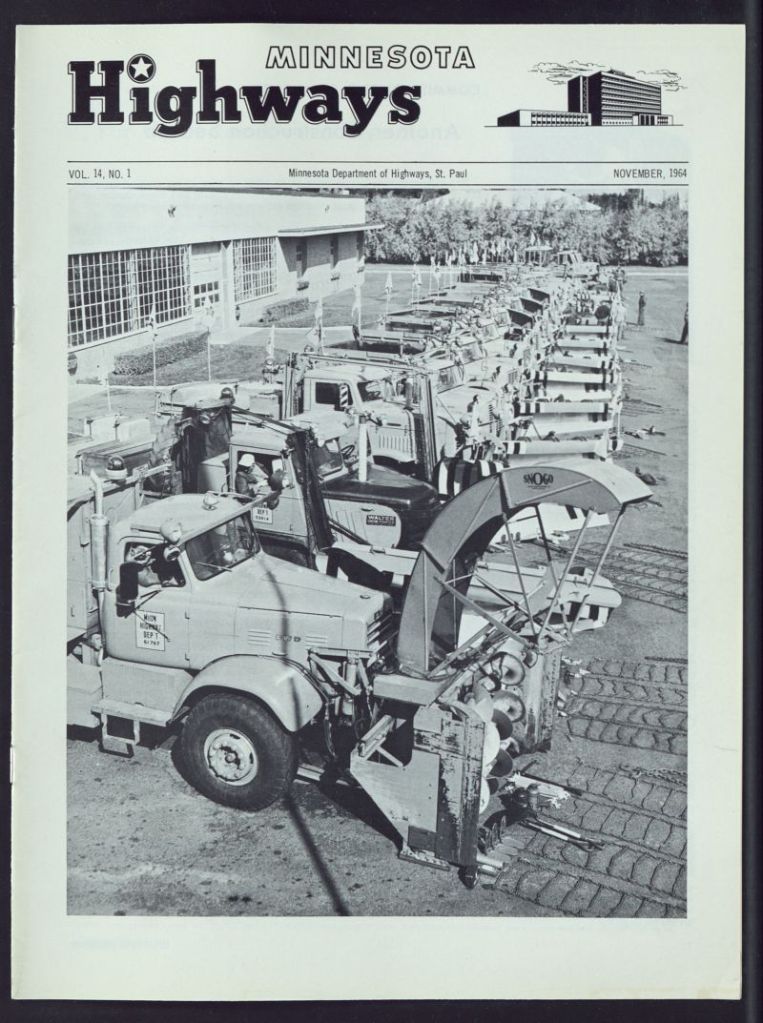

Minnesota Department of Highways. Minnesota Highways, November 1964. 1964-11. Minnesota Department of Transportation, MnDOT Library, collection.mndigital.org/catalog/mdt:5232 Accessed 30 Jan 2026.

When Klay began his career in the early 1980s, plowing and sanding were the dominant winter maintenance practices. Minnesota’s snow and ice control “formula” was straightforward: plow the snow, then apply a heavy mix of sand and salt—often around a 70/30 sand-to-salt blend—to improve traction. Crews relied more on abrasives than chemistry, spreading material after snow had accumulated and temperatures were already dropping. Roads were rarely bare, but they were predictable, and drivers expected winter conditions and adjusted their behavior accordingly.

Over time, however, the widespread use of sand created visible and growing problems. Klay shared stories of driveways and garage floors buried under sand tracked in by vehicles. While communities prioritized spring street sweeping, they were only ever able to recover a fraction of what had been applied. The rest made its way into wetlands, stormwater ponds, lakes, and rivers.

“We’d send out the sweepers in the spring and pick up 800 tons of sand, but we had put out 2,800 tons over the winter,” Klay said. “It was going into people’s yards, their garages, and of course into our waterways. You’d see stormwater ponds installed in the 1980s completely full by the 1990s. It became a major maintenance and water quality problem.”

Beginning in the late 1990s and continuing into the 2010s, many communities shifted toward salt as the primary tool for managing ice. As populations grew, traffic volumes increased, and vehicles improved, expectations around winter road conditions changed. Faster commutes and tighter schedules left less tolerance for snow-covered roads. Salt became the go-to solution—not because it was always the best option, but because it produced quick, visible results.

Bare pavement became the measure of success.

“And now people are upset about road conditions even while storms are still rolling through,” Klay observed. “A few decades ago, folks would look outside and say, ‘I guess we’re not going to work today.’ Now they expect the road to be cleared within an hour or two. Instead of the driver adjusting to winter conditions, the expectation is that the conditions adjust to the driver.”

After several decades of relying heavily on salt, communities are now grappling with the cumulative environmental and economic costs. Chloride from road salt has steadily accumulated in soil, surface water, and groundwater. Across Minnesota, 68 lakes and streams are listed as impaired for chloride, with more than 100 additional lakes nearing that threshold—levels that are toxic to fish, aquatic organisms, and plant communities. Drinking water sources are also becoming saltier: 27 percent of monitoring wells in the Twin Cities metro area’s shallow aquifers exceed EPA chloride guidelines. At the same time, salt accelerates corrosion of roads and bridges, driving millions of dollars in maintenance and repair costs each year.

We’re now at a point where it’s clear that we’ve once again leaned too heavily on a single strategy to manage winter conditions. In response, state and local efforts over the past decade have focused on using salt more responsibly—from smart salting training for winter maintenance staff to public education campaigns aimed at resetting expectations.

One approach that particularly intrigues Klay is pre-treatment, or the practice of applying materials before snow or ice bonds to the pavement. This strategy was virtually unheard of in the 1970s, when limited forecasting and equipment made proactive treatment impractical. Today, improved weather data and modern application tools allow crews to be more intentional—treating roads earlier and more precisely, often reducing the amount of salt needed to manage the incoming storm.

“I worked with a supervisor who was really good at reading storms and loved digging into the forecasts,” Klay said. “He had a great instinct for when to get out and pre-treat the roads. You had to hit it just right, but it saved time and money for the community and made our jobs easier.”

Still, Klay believes that meaningful progress will also require a shift beyond technology—one that includes how we think about winter driving itself.

“We used to know winter required patience,” he said. “That’s not a step backward—it’s just remembering how to live with it.”

Top Image: Bue, Mathias O., 1889-1969. Cars driving on winter roads, North Prairie, Minnesota. 1928. Fillmore County Historical Society, collection.mndigital.org/catalog/fch:170 Accessed 30 Jan 2026.