We’ve entered that in-between phase of winter—the deep freeze of January and February is behind us, but the forecast is an unpredictable mix of snow, sun, rain, and wind. The downside? Keeping the family mudroom organized is impossible. Winter boots, snow pants, light gloves, heavy mittens, thick jackets, thin jackets, mud boots, umbrellas, bike helmets—and my dog’s favorite chew toy, pairs of Crocs—are scattered across the floor. Putting anything away feels futile since it will likely be needed again in the next week.

The upside, at least for me, is watching the landscape wake up from winter. Water is the first to move—melting snow, rainwater pooling into puddles and flowing into storm drains, and the ground thawing (mud season is here!), all signaling the shift toward spring. The energy of these changes is contagious.

As I watch the water flow, I can’t help but wonder—where does it all go? What path does it take? Lately, wetlands have been on my mind. I think of wetlands as nature’s storm drains, but with added benefits. Unlike traditional storm drains, wetlands slow the flow of water, allowing it to gradually seep into the ground or release gradually downstream, reducing the risk of flooding. They also trap sediment, filter/process pollutants, and provide essential habitat for fish, birds, and other wildlife.

Unfortunately, in Minnesota, we’ve lost approximately 50% of our original wetlands due to agriculture and urbanization. That loss comes at a cost—wetlands provide significant economic benefits. According to the EPA, a one-acre wetland can store up to one million gallons of water, helping to prevent flood damage and erosion. Wetlands also play a crucial role in filtering out contaminants like phosphorus and nitrogen before they reach lakes and rivers, improving water quality for both people and wildlife. Additionally, they support a rich diversity of plants and animals, serving as vital breeding and nesting grounds for many species. As we develop more land and add impervious surfaces, it makes financial and environmental sense to work with nature’s engineering rather than relying solely on costly human-made solutions.

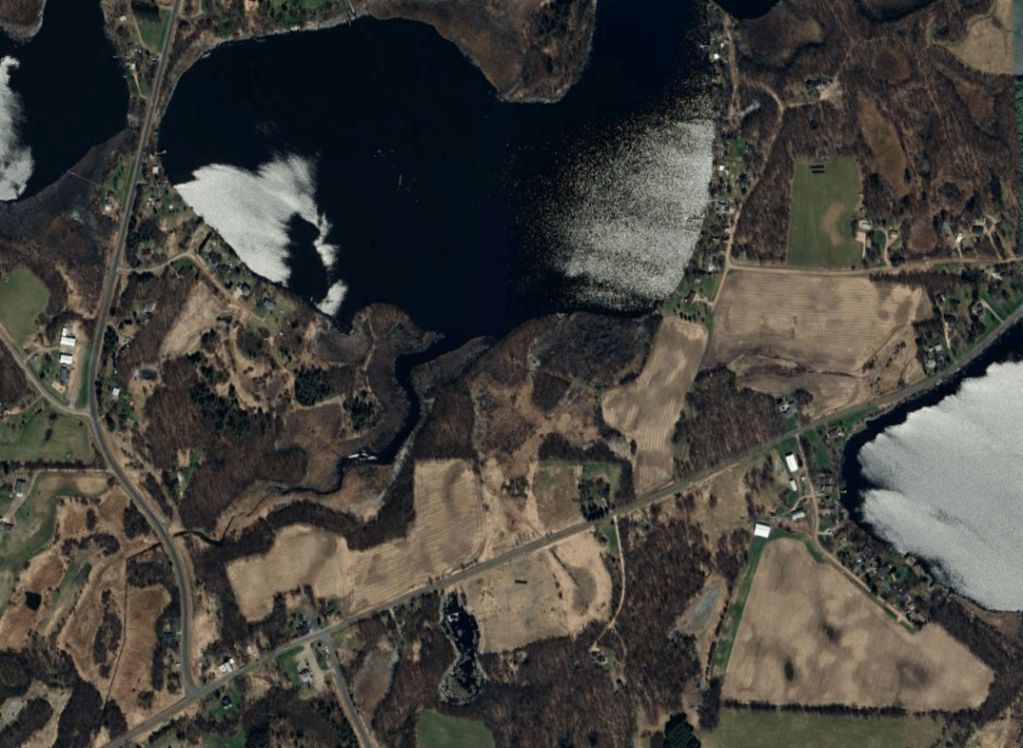

Encouragingly, we’re seeing more private landowners interested in wetland restoration. This past fall, the Lower St. Croix Watershed Partnership helped fund a wetland restoration near Harris in Chisago County. Before European settlement, the landscape was a intricate network of wetlands, but over the last century, agriculture led to extensive draining and ditching in the area. One such ditch runs through Matthew Krousey’s property, draining a former wetland into nearby Horseshoe Lake. Invasive reed canary grass and cattails dominate the basin, limiting the wetland’s function to support wildlife.

Krousey, a local pottery and ceramics artist inspired by nature, wanted to change that. “My work is all about wildlife and habitat—I look at those things and feel inspired,” he says. “So if I can help restore habitat, it just makes sense.”

He reached out to a Minnesota DNR hydrologist, who connected him with Jacquelynn Olson at the Chisago SWCD and Grayson Smith, a fish and wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Together, they developed a restoration plan.

The first step was a “scrape,” removing the top layer of soil containing invasive plant roots and decades of accumulated sediment to restore the wetland’s original depth. Next, they installed a ditch plug and berm at the wetland outlet to allow the area to naturally retain water. A rock spillway was also added to regulate overflow to Horseshoe Lake. Lastly, a pollinator grant funded native plant reseeding to attract bees, birds, and other wildlife.

Beyond restoring wildlife habitat and expanding water storage in the area, the water quality benefits of this project are significant. Estimates suggest it will remove approximately seven pounds of phosphorus per year from the system—a reduction that could prevent 3,500 pounds of algal growth downstream in Horseshoe Lake. That’s a powerful impact for one wetland!

Another valuable aspect of this project has been the strong collaboration between federal, state, and local partners, demonstrating how different levels of government can work together to effectively manage and restore a natural resource. “These restorations work best as a collaborative effort,” Olson said. “Grayson provided the technical expertise since we don’t have a wetland specialist in our office. I worked to help secure project funding through Clean Water funding at the state level, and partnering with a local contractor for the construction work was a great way to support the community.”

This spring, I’m eager to visit the site and see how it’s weathered the winter. Smith expects the 3.5-acre basin to be filled with water, surrounded by emerging native plants. He’s also hopeful that wildlife will return quickly.

“Even throughout the construction phase, I saw herons flying by to check us out—I can’t wait to see what comes to visit this area in the next year,” he said.