Here in Minnesota, we have a mishmash of all sorts of fascinating landscapes – landscapes formed by volcanoes, ones carved by glaciers, extensive shallow beaches that boasted all types of critters for hundreds of millions of years, and massive lakes and rivers that continue to drain all of it. For most, it’s definitely not as exciting to contemplate as Star Wars or the new Barbie movie – but as a geologist, I find the rocks around us are a window into the past, and it is mesmerizing.

That geologic history, particularly those millions of years where much of Minnesota was a warm, shallow beach, continues to serve an incredibly important role in our everyday lives, although most likely don’t realize it. Those beach sediments solidified into layers of sandstone and limestone, and sandstone in particular has a great capacity for storing and holding water. Today, all the water we use for drinking, watering our lawns and gardens, in agriculture, and largely across industry comes from those ancient sandstone deposits tens to hundreds of feet underground. Yep, I’m talking about groundwater.

Yet, even though groundwater is technically ‘out of sight, out of mind,’ it still is very much connected to what we do at the land surface. Pollutants or contaminants can slowly leach down into groundwater from the surface, coming from a variety of different sources. Many of those pollutants you’ve likely already heard about – chloride, nitrates, and there’s a lot of media right now about the emerging contaminant PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) that are generated in manufacturing certain products and are considered ‘forever chemicals’ because they do not break down.

Here’s a broad brush of the most common groundwater pollutants you’ll hear about in Minnesota:

Industrial and/or commercial activities:

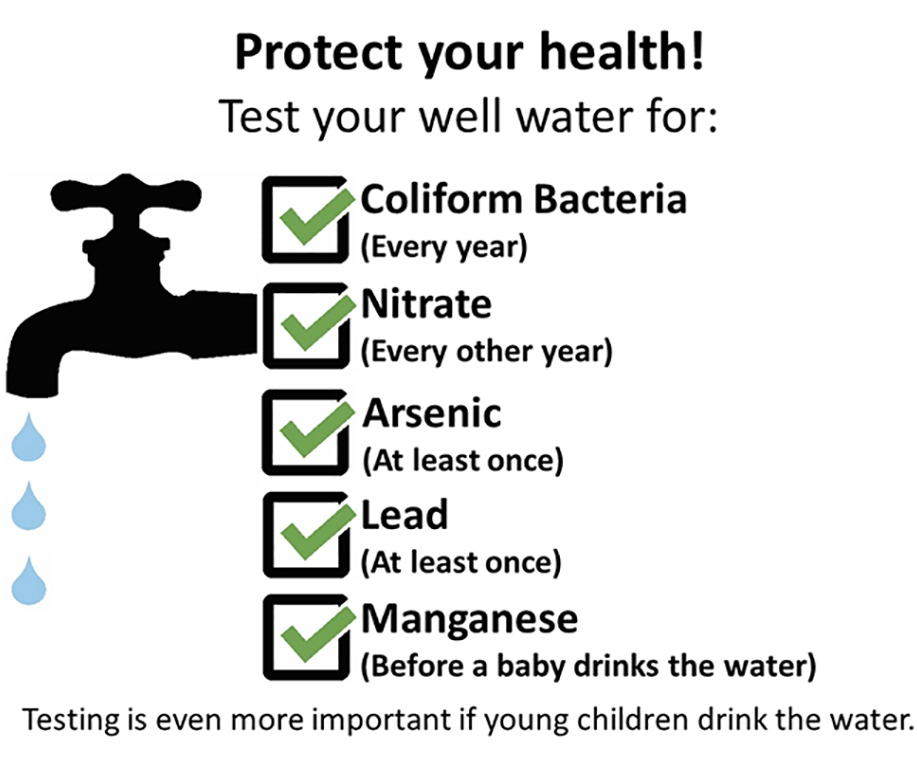

- Heavy metals from mining and improper waste disposal can introduce contaminants such as lead, mercury, and cadmium into groundwater.

- Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) like benzene, toluene, and trichloroethylene can result from leaky fuel storage and improper disposal of chemicals.

- Chloride from use of road salt in the winter can impact water quality in both our waterways and groundwater.

- Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, more widely known as PFAS, are generated largely in manufacturing firefighting foam, non-stick coatings, and more.

Agricultural or more rural applications:

- Nitrate contamination can result from the wide use of fertilizers and manure on our farm fields, resulting in impacts to drinking water quality as well as posing health risks, especially for infants and pregnant women.

- Pesticide use in agriculture and landscaping can lead to groundwater contamination.

- Failing septic systems and inadequate sewage treatment can lead to bacterial or viral contamination, posting a risk to human health.

Natural contaminants:

- Naturally occurring arsenic can be present in groundwater and can have serious health effects on those who consume contaminated water over an extended period.

- Iron and manganese are minerals that also occur naturally in groundwater – while not usually harmful in small amounts, they can affect water taste, color, and odor.

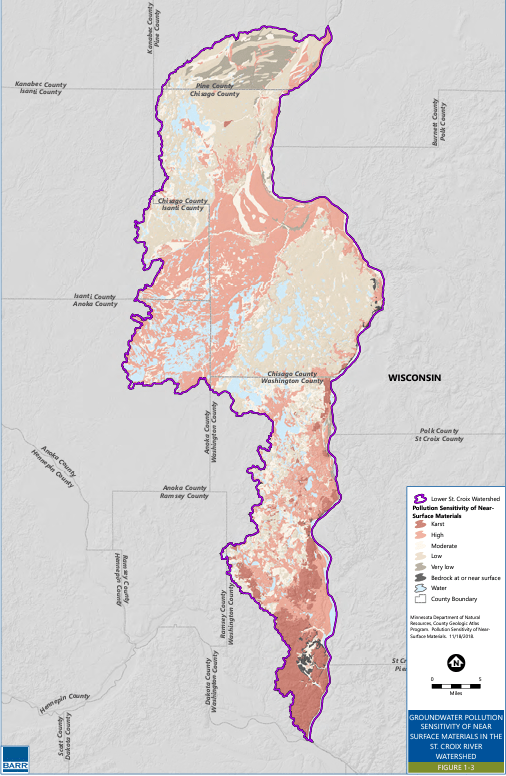

One important thing to note when considering groundwater pollution is that not all landscapes are created equal – based on the elevation of the water table (defined as the level where all the pores in the subsurface are saturated) and the type of rock or sediments at or under the land surface, pollutants can have a preferential pathway to our groundwater.

For instance, in the Lower St. Croix watershed, we have several areas that have greater ‘sensitivity’ to groundwater pollution due to the ability of water-borne contaminants to move quickly (hours to weeks) from the land surface to our groundwater aquifers.

In those areas of greater sensitivity, the onus is on municipalities and those on private wells to best manage contaminants that may likely occur due to land use practices in the area. The Minnesota Department of Health recommends regular testing of private well water to ensure its safety and quality.

We are working with conservation professionals in Washington and Chisago counties as well as the Minnesota Groundwater Association and Minnesota Well Owners Organization to host two well water screening clinics in September. Residents from across the basin can bring in a sample of their drinking water (at least 1 cup (8oz) in a hard plastic or glass container) and have it tested onsite for chloride and nitrates. No reservations are needed, and staff will be available to consult with residents one-on-one to discuss concerns and help suggest additional testing if needed. If you are a well owner, we hope to see you there!